Book on The Köln Concert written by Peter Elsdon

Published by Oxford University Press

In this only known extensive study of The Köln Concert, Peter Elsdon exposes a broad picture of the repercussion of The Köln Concert from its musical content to its cultural and historic meanings.

Elsdon by no means limits himself to conduce his narrative exclusively on this successful solo concert. Rather, he makes references to other solo piano works by Keith Jarrett, so as Jarrett the Jazz musician in the scope of other important Jazz pianists of the time, such as Lennie Tristano, Cecil Taylor, Paul Bley, Richie Beirach, to name a few.

Elsdon provides the readers -

Moreover, Elsdon’s book is a thoughtful provoking study, but by no means a complete study. The book would have been further more elucidating had Elsdon provided a final chapter either with the participation of a modern musicologist or else, Keith Jarrett himself, discussing some aspects of The Köln Concert in an open dialogue. In such a case, the participant in the discussion would have to be (in my view) already well acquainted with Elsdon’s manuscript.

Regardless Elsdon self narrative approach, despite countless references quoted in his study, his book remains partial for two main reasons that I would briefly like to expose: one has to do with the common notion accentuated in the book that The Köln Concert recording is a Jazz solo album. The other notion, even more inaccurate, is the categorization of Keith Jarrett as being a Jazz piano musician rather than a musician who plays Jazz.

I, in fact, would like to start exploring the second notion of Jarrett as a Jazz musician, before going into the notion of the music of The Köln Concert as Jazz.

Take for instance the year of 1976, which remains perhaps the most prolific year of documented recordings of Jarrett’s career: in April he recorded with the American Quartet The Survivor’s Suite in a studio in Ludwigsburg, in May he recorded with the same quartet Eyes of the Heart live in Bregenz, also in May he recorded the solo piano album Staircase at the Davot Studio in Paris, in September he recorded the organ works Hymns -

Whether or not you the reader are familiar with the recording of the Hymns and Spheres, it is at this point relevant to mention that the Hymns -

The Hymns -

And with the same indignity, I will also assure you that if you were Keith Jarrett and sat at a harpsichord with the self notion that you were a Jazz pianist, you would not be able to play with any convincing competence The Goldberg Variations or the complete Well Tempered Clavier Book Two by J. S. Bach either!

The fact that Jarrett decided to pursue an interest in Jazz in his teens to eventually become known as a Jazz musician, is to an extent, circumstantial. He started learning to play the piano at age three under a traditional Classical European approach. By the age seven, he was performing at a solo recital works of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelsson, Brahms, Moussorgsky, so as his own compositions.

When we consider the fact that Jarrett was raised in Allentown, a modest town in America with hardly any cultural life, one can only imagine how differently it would have been if he had, for instance, been raised in New York City attending the Philarmonic, so as recitals of well known classical pianists such as Arthur Rubinstein, Rudolf Serkin, Claudio Arrau and the like.

Jarrett as a young boy had some personal challenges as well. His parents divorced when he was still very young, and from that point on, he and his four younger brothers were raised without their father. It seems that his encounter with Jazz later as a young teenager, played a decisive role in the direction of the course of his fate. For Jazz became a way for his self expression, where as a composer and improviser, his imagination and intelligence flourished with inspiration and originality. And within this quest, the young Jarrett had found a purpose for himself, a way of surviving and living creatively.

It seems that Jarrett never left Classical music so to speak. Apparently during his formative years in the 1960s establishing himself as a professional player between Boston and New York, he may have focused his efforts primarily in Jazz. But once he settled down and began a family living in New Jersey, he was again tempering with the piano repertoire of Classical composers. Moreover, from the time he embarked in his improvised solo concerts in the early 1970s to this day, his primary means of preparing for his solo concerts (aside of the cumulative experience) has been practicing the piano works of Classical composers. -

In addition, Jarrett’s years from 1984 to 1995, in which he extensively performed and recorded Classical Music along a number of his own chamber music works composed and recorded prior and during those same years, speak for themselves. [More recently in 2010, Keith Jarrett recorded (on the piano) with violinist Michelle Makarski the six sonatas for violin and harpsichord by J.S. Bach]

Now lets turn our attention to the recording of The Köln Concert, if I may.

Perhaps the most imprinted association with the recording of The Köln Concert is the image of Keith Jarrett on the art cover of the album. As Elsdon has described, Jarrett at the piano with his head bowed into his chest and his eyes closed, can be viewed as richly evocative. Whether the image of Jarrett in a state of introspection on the cover suggests a link to a state of spirituality, is opened for interpretation. However, his completely immersion in his playing is without a doubt revealing. By contrast, the image on the back of the album provides to those discovering Jarrett and listening to The Köln Concert for the first time, a sense of a surprising impression when faced with his youthfulness and the genuineness of his playing. And even though the moments captured through the lens of the photographer Wolfgang Frankenstein are actually not images from The Köln Concert event, they are still revealing though. For instance, the jeans outfit which Jarrett is seen wearing, provides an outlet for a time frame in cultural history. For where one can identify elements of Jazz in Jarrett’s playing in The Köln Concert, the jeans outfit is a direct representation to those same elements as part of that historic Jazz-

Yet, an important question remains: how much of The Köln Concert is indeed Jazz?

Based on the outline structure of Part 1 of the concert provided by Elsdon, we have the following classification:

Chronological references from The Köln Concert to the evolution of African-

African and Middle Eastern Elements

Austro-

Bach Haydn Mozart Schubert Beethoven Mendelssohn Brahms Hindemith

Course of History

Jazz

Time

0’:00”

2’:12”

2’:52”

7’:42”

8’:40”

9:44”

14’:14”

15’:06”

16’:35”

17’:45”

21’:13

Part

Opening

Vamp

Rhapsodic passage

Phase 1, rhapsodic

Phase 2, groove

Phase 3, rhapsodic

Phase 4, groove

Ballad passage

Choralelike

High-

Melodic statements in 8vas

Groove passage

Tonality

Am/G

B Locrian

Am/G (ostinato)

Am/G (ostinato)

Am/G (ostinato)

Am/G then Am/G/F/E7

E Flat to other Flat keys

C minor area

A major (D/E implied)

Description

Steady, opening theme expands

Vamp figuration, nonthematic

Rubato, long elaborated lines

Steady, descending theme

Rubato, lines more chromatic

LH ostinato, then octaves

Exploratory

Vamp

Time

0’:00”

4’:34”

5’:50”

7’:09”

7’:57”

11:24”

12’:13”

12’:54”

13’:21”

14’:04”

14’:36

Part

Vamp

Breakdown, vamp again

Breakdown, vamp again

Transition

Chorale/expansion

Ballad

Tonality

D Major

D minor area

F sharp minor

E minor

A flat pedal

Modulating

Description

Expanding texturally

RH theme in octaves

Increasingly dissonant and dense

Ascending / descending chords

Pause on high-

Time

0’:00”

6’:09”

6’:37”

8’:12”

11’:22”

13:34”

14’:08”

15’:07”

Part

Vamp

Transition

Repetitive

Chorale/coda

Tonality

F sharp minor

From F sharp minor

through a series of keys

A flat major (Lydian)

A flat major (Lydian)

A flat major

D flat (Lydian)

Description

Oscillating 16th notes, broadening

gradually

Expansive piano figuration

Settling onto a single harmony

Settling onto A flat again

Chorale figuration gives way to

rhapsodic RH lines

RH lines over sustained D flat

sonority

Interestingly, the diagram also displays -

From the Jazz Playing category we can trace many trends within the evolution of Jazz:

Part 1: Modal Jazz (a later trend in Jazz) ► Boogie Woogie ► Be Bop ► Gospel Chorale

Part 2a: Jazz piano with African influences

Part 2b: Post Be Bop with Middle East influences

Part 2c: Gospel Chorale

Proceeding from the Jazz Playing category, the Outside Jazz Playing category remains essentially within the Austro-

It is possible to speculate that Jarrett’s conscious intent was to improvise The Köln Concert relying primarily in his Jazz Playing, as he had done in some previous concerts. Furthermore, when we trace back the transmissions of each part of the concert, we find that each main part is initiated and derived from early elements of music history within the Jazz Playing category:

Part 1: Greek Music

Part 2a: African Music

Part 2b: Arabic Music

Now, why does Jarrett deviate the music from Jazz to European Music tradition over and over again throughout the main courses of the concert? There are a few speculative hypothesis to consider, if I may:

1) Jarrett was expanding his solo concert vocabulary by gradually relying more in his early Classical Music training;

2) Jarrett was in Germany playing for a predominant German audience at an Opera House;

3) Jarrett was playing an Austrian made Bösendorfer piano;

4) Jarrett is an Austrian descendant;

5) Jarrett is also a French-

Although the last four hypothesis may seem nonsense or even absurd, they can’t be disproved so easily either!

Early in his book, Elsdon stated that the factors contributing to the enormous success of The Köln Concert recording were most clearly found in America, the country in which Jarrett lived and worked, and with which he was most associated. This statement by Elsdon -

For him to focus part of his comprehensive thesis in the repercussion of The Köln Concert in America, is without a question a valuable research effort. As for him to claim that the enormous success of The Köln Concert recording is due to America, one would still have to find out from ECM records (the label associated with the recording), what percentage of the 3.5 million records sold reflects the sales’ number in America.

Despite the fact that Jarrett lives in America is not a direct correlation to where he works either. Since the release of The Köln Concert in 1975, Jarrett has played hundreds of solo concerts in Europe and Japan, comparing with a few dozens in the United States. And except for a few recordings in America, his discography has been produced almost exclusively in Europe and Japan since 1975.

Also disputable, would be the notion that Jarrett’s solo concert audiences in Europe and Japan, within countries where he is so well established, are presumably of Jazz advocates. I, for instance, have encountered a number of people in the last thirty years who love The Köln Concert and yet have little or no interest in Jazz. And more ironically, they see the music of The Köln Concert as a music of a new age!

In order for us to understand the broad reception of the recording of The Köln Concert in all the Americas, Europe, Japan, (more recently South Korea), Russia, Africa and the Middle East, we must consider what is aside from Jazz, the nature of its universal appeal.

Likewise, we cannot underestimate the pianistic skills and musicianship of Keith Jarrett in The Köln Concert. For the amusement of listening to his virtuosity and choreographic dexterity in the immediacy of the music, is an universal experience as watching the gymnast Nadia Comaneci during the Olympics of 1976 in Montreal. Curiously, it is rather the psychological apprehension of our experience witnessing the archetypal persona of the artisan in the given moment, that carries us to a state of consciousness which conveys a sense of return in time. Suddenly, we find ourselves wobbling in the core of our own origin, in the enigma of our own evolution. And this complex process, may very well explain the distinctiveness and power of works of art and supreme executions, so as The Köln Concert.

The review of Keith Jarrett’s The Köln Concert by Peter Elsdon is part of my own lecture on The Köln Concert work.

Alexi Lima

Once again, if we are to assume that from the beginning of Part 2a, to the end of the transition at 7’:56”, we have been listening to Jazz, I would argue to whether any content from 7’:57 to the end of Part 2a at 14’:36”, is by any means directly related to Jazz. It is curious to notice that the first 7’:56” of Part 2a remains one of the most rare and extraordinary display of African piano playing by Jarrett in his documented discography!

For the outline structure of Part 2b provided by Elsdon, we have the following classification:

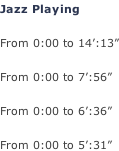

If we are to assume that from the Opening of the concert to the end of Phase 4 groove at 14’:13’’ before the beginning of the Ballad passage at 14’:14’, we have been listening to Jazz, I would argue to whether any content from 14’:14” to 21’:13” or beyond,, is by any means directly related to Jazz. In fact, the Rhapsodic passages from 2’:52” to 7’:41’, could well be considered Baroque keyboard music played in a jazzistic manner.

For the outline structure of Part 2a provided by Elsdon, we have the following classification:

Finally, if we are to assume that from the beginning of Part 2b to the end of the transition at 6’:36”, we have been listening to Jazz, I would argue to whether any content from 6’:37” to near the end of Part 2b before 15’:10” is by any means directly related to Jazz.

And the remaining Part 2c of the concert is without an argument Jazz in its entirety.

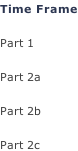

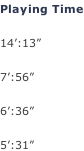

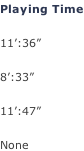

In summary, if we are to categorize the concert in two classifications, we can divide it into Jazz Playing and Outside Jazz Playing as follow:

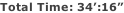

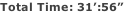

When we look at the total time of Jazz Playing time and the total time of Outside Jazz Playing time, we find that for the two categories, 34’:16” of the concert is Jazz Playing while 31’:56” of the concert is Outside Jazz Playing. (Admittedly, the passages in the last two minutes of Part 2b have Jarrett’s own saxophone playing influence, but they hardly establish any ground for a Jazz context.

Now, the implications for this division are relevant when discussing the concert for two main reasons: Firstly, we need to ask what is the nature of the music Outside Jazz Playing? Secondly, why the three main parts of the concert tend to evolve from Jazz Playing to Outside Jazz Playing?

The diagram below displays the over all transmission of The Köln Concert within the classifications of the two broad categories of Jazz Playing and Outside Jazz Playing already presented earlier on the page of The Köln Concert Masterpiece: